Please welcome Nathan Schaper, a devoted volunteer of Sustainable Hamilton Burlington and Sustainability Leadership, who is an engineer, cycling enthusiast and our guest blogger for this month’s post.

Committing to sustainability is an important first step, but what comes next and how to start fulfilling sustainability commitments? One simple way to start is through procurement; in fact, it only requires a small change in mindset and a few minimal changes in evaluating the value of your suppliers products or services. Historically, procurement has been based on only two criteria: price and quality. However, forward-thinking companies have been creating market advantages by incorporating the triple bottom line into procurement decisions: economic, social and environmental considerations. Sustainable procurement initiatives can evolve from the dedication to sustainability through sustainability reporting. It aligns well with four Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): SDG 3 – good health and well-being, SDG 8 – decent work and economic growth, SDG 12 – responsible production and consumption, and SDG 13 – climate action.

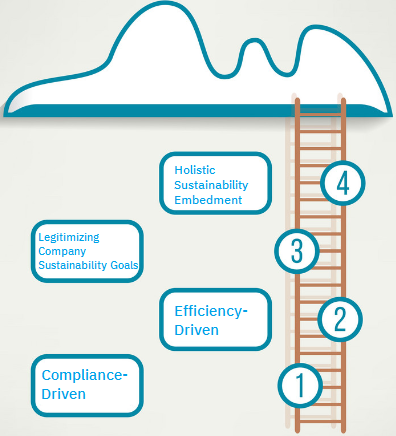

The business case for sustainable procurement is very strong. A business can reinforce their mission and values, fulfill sustainability goals, foster innovation, save money, improve brand reputation, satisfy customers and stakeholders, better understand their products and services, strengthen supplier relationships and performance, improve supply chain resilience, and establish business leadership in an increasingly climate aware society, all with a few simple changes to procurement (World Wildlife Fund, n.d.). According to the World Economic Forum, there are four steps on the sustainable procurement ladder as shown in Figure 1 (World Economic Forum, 2015). Which step is your company at?

Figure 1: Sustainable Procurement Ladder

Supply Chain Resilience.

Sustainable purchasing creates resilience in the supply chain. Following last month’s theme of resilience, there is inherent risk in supply chains, including costs associated with supply chain disruptions, product recall and late delivery penalties. Furthermore, there are indirect costs such as brand reputation and product boycotts (Lefevre, Pellé, Abedi, Martinez & Thaler, 2010). One way to increase company resilience is to localize and simplify supply chains. When purchasing sustainably, those gains are carried forward to company output, resulting in sustainable branding opportunities and competitive advantage in the face of risks. It is far easier to ensure the security of supply if suppliers are similarly engaging in sustainable practices, increasing total supply chain resilience.

Environmental Procurement.

It is important to start by analysing company environmental sustainability goals and find where they align with sustainable purchasing. For example, sustainable purchasing can be an essential part of meeting corporate environmental goals such as reducing waste, pollution and emissions. According to the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), scope 3 corporate emissions (indirect emissions), are on average 4 times higher than scope 1 (direct operational emissions) (CDP Report, 2015). Furthermore, much of those emissions can be attributed directly to supply chains; Hewlett Packard (HP) found 99% of their emissions come from scope 3 emissions, and 50% of emissions from their supply chain (HP Development Company, 2020). Here are four places to begin tackling environmental sustainability in procurement:

- Type of materials being procured.

- Material properties of the procured items (recycled content).

- Transportation distances from the supplier.

- Transportation fuel used (Mantle Developments, 2020).

Materials & Circularity.

One of the main ways to increase sustainability is to look directly at the materials used in operations and consider implementation of various stages of circularity. For example, IKEA adapts their procurement model around the 4 circular loops of their supply chain: reuse, refurbishment, remanufacturing, and recycling (IKEA, 2019). With this at the heart of their procurement strategy, IKEA ensures the consideration of a circular supply chain option when choosing suppliers and developing their products (IKEA, 2019). This reduces costs of packaging, waste disposal, operations, and keeps the company ahead of regulators. One easy way to start is in packaging; where reducing, reusing or incorporating biodegradability does not disturb operations and can reduce costs. Creating a circular supply is especially important given the impending single-use plastics ban to be implemented this year, 2021, which will gradually increase the restricted plastic products in the future (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2019). Once packaging has been addressed, it could be time to request suppliers to maximize the use of post-consumer or recyclable material into products themselves, and design products for longevity by improving product durability, reparability, reusability and upgradeability. Xerox in 1993, demonstrated this in their remanufacturing processes, where they started to collect recycled printers/copiers and cleaned, repaired and reused those recycled parts in new products, saving them several hundreds of millions of dollars in supply costs (Xerox Corporation, 2007). By procuring for these types of products, or identifying opportunities to retrieve these products as by-products from other areas of your own operations, you are effectively designing a circular supply chain from which to take advantage of (Sustainable Procurement, 2006).

Another way to look at the environmental pillar of procurement is to start by creating a profitable circular product stream instead of paying for disposal. This often requires out-of-the-box thinking, partnerships, and long-term planning; starting with procurement of reusable products and materials. With changing regulations such as the introduction of Ontario’s Extended Producer Responsibility, companies will start to bear 100% of the operating costs of the blue box program. This responsibility starts for some producers by 2023 and expands to all producers in 2025 (Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, 2019). This means that these additional costs of disposing materials will be transferred up the supply chain and force cost cutting somewhere else in operations. Taking a proactive approach to sustainability in your procurement processes means that you are mitigating these rising costs and the accompanying risks. Our very own member company REfficient is demonstrating the business case and corporate demand for circular products as they extend the life of telecommunication products. REfficient has capitalized on creating their own circular economy, embedding this strategy into the core of its business operations. All organizations can increase environmental sustainability just by addressing materials already used in operations, and using circular economy principles to extend product lives.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions.

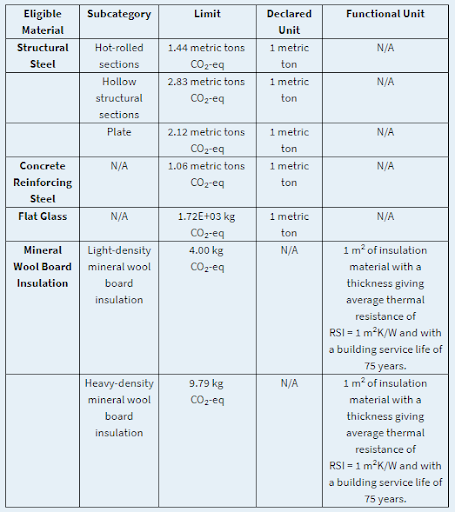

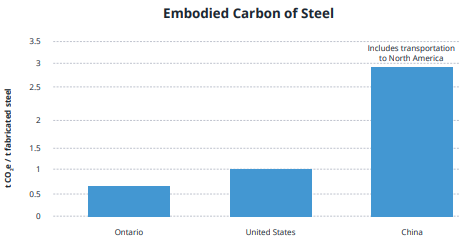

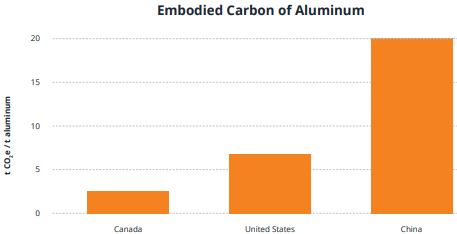

Another part of a good corporate sustainability strategy is a plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (commonly referred to as “carbon”). When reducing carbon emissions associated with procurement, it is necessary to track the entire product life-cycle. One way to track emissions is to obtain Environmental Product Declarations (EPD) which contain product information including all emissions associated with the product extraction through to the current state in the life-cycle of the product, called embodied emissions or embodied carbon. To even further understand the life-cycle of a product or material, it may be useful to conduct a life-cycle assessment (LCA) using one of many online tools, such as OpenLCA. Governments are taking action to reduce embodied carbon by developing new policies and regulations to monitor and control embodied carbon, leaving those who don’t limit their embodied carbon when selling products uncompetitive and restricted in certain markets. As part of the Buy Clean California Act, the state of California is setting government purchasing embodied carbon limits on certain products starting July 1, 2021, see Figure 2 (State of California, 2021). Closer to home, Vancouver plans to reduce embodied emissions from new buildings by 40% in 2030 (Vancouver City Council, 2021). According to the Globe and Mail, border carbon adjustments (where border tariffs are imposed to ensure adherence to local carbon prices) are gaining traction worldwide (Radwanski, 2020). Furthermore, the European Union (EU) is proposing border carbon adjustments as part of their COVID relief bill, meaning low-carbon products are likely to avoid fines and tariffs while products above regulated thresholds of embodied carbon are exposed to those fines and tariffs (General Secretariat of the Council, 2020). There are benefits to reducing the embodied carbon in procurement, as it helps to reduce Scope 3 emissions found in upstream your supply chains, reducing embodied emissions of your own products and services.

Canadian Advantage.

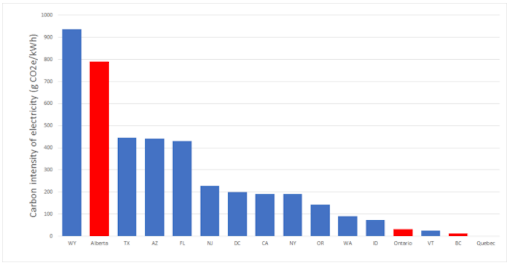

There is significant carbon reduction simply by choosing to buy Canadian instead of international. There is likely significantly smaller costs and carbon footprint for transportation, especially when collaborative strategies are used to aggregate shipments and maximize loads. The Canadian advantage is more pronounced when factoring in the carbon intensity of the Ontario electricity grid, which is significantly decarbonized compared to other jurisdictions, Figure 3. Producers relying on a relatively decarbonized energy grid for their manufacturing and operations, produce products with less embodied carbon. Furthermore, Figure 4 shows the relative embodied carbon of two common materials in Canada which is less than American equivalents and significantly less than other traditional markets like China (Blue Green Canada, 2021). Take advantage of the opportunity that this creates and increase market competitiveness by leveraging the sustainability advantage Canada provides. Consider further increasing sustainable operations using less carbon-intensive steel from SHB’s very own member ArcelorMittal Dofasco and other Hamilton-based material companies for upcoming projects.

Figure 2: California embodied carbon limits (State of California, 2021).

Figure 3: Carbon Intensity of electricity (Mantle Developments, 2021).

Figure 4: Embodied carbon of steel and aluminum (Blue Green Canada, 2021).

Societal Procurement.

Social sustainability is another important part of a good sustainability plan and is just as important to have social values represented in procurement as well as environmental values. Social procurement focuses on human health, participation, transparency, resource security and sustainable communities (Environmental Protection Agency, 2015). There are some significant ways to ensure social sustainability in a supply chain on top of the current Canadian advantage of strong social, labour and human rights laws. Local businesses are often already offering sustainable versions of common products, and making connections with other local businesses can lead to increased profitability for both parties and the local economy.

Local Business.

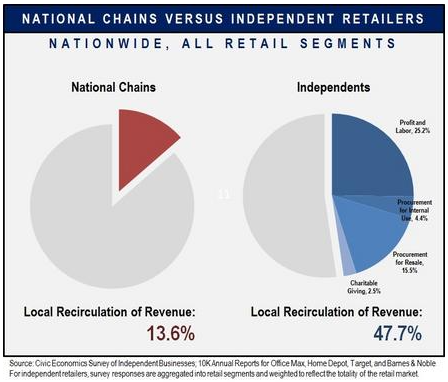

There are numerous societal impacts to supporting the local economy, especially in these trying times. Thriving communities are often supported by the backbone of local businesses, (Patel, n.d.) especially now with 20% of Ontario businesses at risk of closing due to COVID-19 and 31% of Canadian small businesses at pre-pandemic sales, it is a particularly important time to support local (Canadian Federation of Independent Business, 2021; Small Business Recovery Dashboard, 2021). Buying from local Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) creates local jobs; according to Statistics Canada, SMEs (1-499 employees) employed 89.5% of private-sector workers (Government of Canada, 2019). Further, SMEs contributed 54.9% of the 2015 Canadian GDP compared to large businesses (Government of Canada, 2019). Small businesses are essential to our economy and offer many unique niches to each community they are a part of which generally is not found with larger businesses. SMEs are often the identity of communities, and they can define the way communities develop over time; they are often what makes our home communities distinct and important to the people living there (Patel, n.d.). Civic Economics has completed many studies looking at the local impact of national chains vs independent retailers and has consistently found that independent retailers contribute over three times as much to the local circulation of revenues, Figure 5 (Civic Economics, 2012). There are thousands of small businesses providing niche products in the GTHA, by partnering and procuring from local businesses, your own organization increases its presence in the local community. When buying from local businesses, more money stays in the local economy boosting the tax base, increasing local services and community wellbeing, and can lead to an increase in customer potential for your own business, when sharing the wealth comes full-circle.

Canadian Advantage.

Sustainable procurement includes making those connections with your suppliers and having collaborative dialogue to improve quality, standards and policies when undertaking sustainability strategies and initiatives together. It is easier to create that lasting, sustainable bond with suppliers that are nearby. Local businesses can also much more easily pivot to involve additional sustainable business practices and in many cases are already offering great sustainable alternatives. Furthermore, buyers can more easily work with local suppliers throughout disruptions, in contrast to large international suppliers that may prioritize larger clients and leave buyers without supplies when they need it most (Business Link UK, 2009). Embrace the unique products Canadian companies have to offer and consider the benefits that Canadian companies have when purchasing.

Figure 5: National vs independent (Civic Economics, 2012)

Take Action.

There are two main approaches to take when considering implementing sustainable procurement: product-based and supplier-based. The product-based approach requires tracking a certain product through the supply chain to understand the impacts of the product: e.g. product life cycle analysis or on-site audits. The supplier-based method addresses the ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) practices of the suppliers making the products: e.g. sustainability reporting, B-Impact assessments, questionnaires and/or standards. One or both of these methods can be used to ensure a strong commitment to the social and environmental aspects of procurement.

6 Steps.

These 6 steps can help start a corporate sustainable procurement journey:

Step 1: Get the decision-makers together (green team, procurement team & senior executives)

Step 2: Set goals (including meaningful metrics and key performance indicators)

Step 3: Map out a procurement policy and strategy (Model Policy from Sustainable Purchasing)

Step 4: Develop tools and procedures (RFP & procurement requests ESG clause, make use of globally recognized sustainability seals such as ISEAL Alliance)

Step 5: Engage and collaborate with suppliers (inform suppliers of your new priorities and look for common ground on environmental and social issues)

Step 6: Track progress and pivot as needed (Credit Union Central of Canada, 2011; World Wildlife Fund, n.d.).

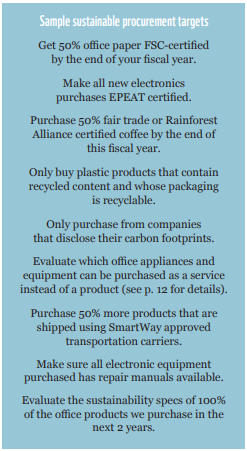

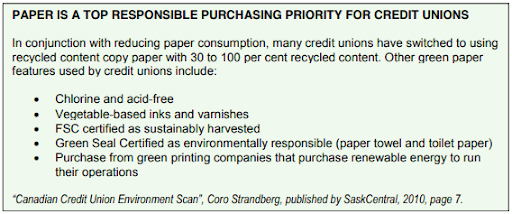

The most important part of implementing sustainable procurement at your company is to detail how sustainable procurement offers improvement to an economically vital part of the company such as revenue, market share and overall procurement spending and create a business case for sustainable procurement (Sustainable Purchasing Leadership Council, n.d.). See Figure 6 for some sample procurement goals and Figure 7 for tips on one of the easiest places to start: paper.

Some of the global best practices in sustainable purchasing documented by the Co-operators are:

- Incorporating social and environmental criteria into RFP’s for all suppliers.

- Require suppliers to complete a sustainability questionnaire and sign a Supplier Code of Conduct.

- Social and environmental criteria are used as a factor in the evaluation process (ex. 10% weight).

- Staff training on sustainable purchasing. Such as through the Sustainability Leadership Program.

- Reporting on sustainable results and impacts.

- Engagement of suppliers through workshops, websites, and forums (Strandberg, 2010).

Figure 6: Sample Sustainable Purchasing Targets (World Wildlife Fund, n.d.)

Figure 7: One easy place to start is paper (Credit Union Central of Canada, 2011).

Conclusions.

Business sustainability can be attained through various initiatives, one of which is procurement. Sustainable procurement creates cost-effective solutions while improving organizational competitiveness, marketability, and best practices. By embedding sustainable procurement practices into procurement strategy, you can reduce risks from changing regulations, take advantage of opportunities and market trends to incorporate low embodied carbon materials into your operations, experience cost-savings by incorporating circular economy practices, and increase marketability to consumers by developing local partnerships and supply chains. In doing so, your organization can take significant steps toward implementing sustainability practices. Clearly, businesses can address the triple bottom line of economic, social and environmental goals when purchasing sustainably. Now with the tools to build sustainability into organizational practices, the only question is…when to start?

References.

HP Development Company. 2020. Purchasing the Future You Want: A Sustainable IT Purchasing Guide. HP Development Company. Retrieved from https://h20195.www2.hp.com/v2/GetDocument.aspx?docname=c07023857

World Economic Forum. 2015. Beyond Supply Chains: Empowering REsponsible Value Chains. World Economic Forum. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEFUSA_BeyondSupplyChains_Report2015.pdf

CDP Report. 2015. Committing to Climate action in the Supply Chain. CDP Report December 2105. Retrieved from https://b8f65cb373b1b7b15feb-c70d8ead6ced550b4d987d7c03fcdd1d.ssl.cf3.rackcdn.com/cms/reports/documents/000/000/580/original/committing-to-climate-action-in-the-supply-chain.pdf?1470053398

IKEA. 2019 Sep 18. Designing for Circularity and our Future. IKEA. Retrieved from https://newsroom.inter.ikea.com/publications/all/design-principles-for-circularity/s/20f17dff-c43f-46c9-a5d4-be766859b760

World Wildlife Fund. n.d. Buying Responsibly. Living Planet @ Work. Retrieved from https://atwork.wwf.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/05/0260_WWF_at-work_toolkit_procurement_FINAL.pdf

Sustainable Purchasing Leadership Council. n.d. Making the Case for Investment in Your Company’s Sustainable Purchasing Program. Sustainable Purchasing Leadership Council. Retrieved from https://www.sustainablepurchasing.org/public/SPLC_Full%20Layout_Digital_051719.pdf

Randwanski, A. 2020 Oct 16. Why carbon tariffs could be coming to Canada soon. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/commentary/article-why-carbon-tariffs-could-be-coming-to-canada-soon/

General Secretariat of the Council (Eds.). (2020). Special Meeting of the European Council Conclusions. Retrieved from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/45109/210720-euco-final-conclusions-en.pdf

Strandberg, C. (2010). International Scan of Sustainability Practices of Insurance and Non-insurance Companies. The Co-operators Group Ltd. Retrieved from https://www.cooperators.ca/~/media/Cooperators%20Media/Section%20Media/AboutUs/Sustainability/best-practices-report.pdf

Credit Union Central of Canada. (2011). Credit Union Social Responsibility Tool: Responsible Purchasing Guide for Credit Unions. Credit Union Central of Canada. Retrieved from https://corostrandberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/purchasing-guide-for-credit-unions.pdf

Lefevre, C., Pellé, D., Abedi, S., Martinez, R., & Thaler, P. (2010). Value of Sustainable Procurement Practices. PwC, EcoVadis & INSEAD. Retrieved from https://sustainable-procurement.org/fileadmin/templates/sp_platform/lib/sp_platform_resources//tools/push_resource_file.php?uid=4d7f2885

Sustainable Procurement. (2006). Sustainable Procurement. UN Procurement Practiotioner’s Handbook. Retrieved from https://www.ungm.org/Areas/Public/pph/ch04s05.html

Mantle Developments | Buy Clean: Create Local Jobs & Cut Carbon Pollution. (2021). Mantle Developments. Retrieved from https://mantledev.com/insights/buy-clean-local-carbon-pollution/

BUY CLEAN: How Public Construction Dollars Can Create Jobs and Cut Pollution. (2021). Blue Green Canada. Retrieved from http://www.bluegreencanada.ca/sites/default/files/Buy%20Clean%20How%20Public%20Construction%20Dollars%20Can%20Create%20Jobs%20and%20Cut%20Pollution%20%28Eng%29%20%282%29.pdf

City of Vancouver Report. (2020). Vancouver City Council. Retrieved from https://council.vancouver.ca/20201103/documents/p1.pdf?_ga=2.174176743.439937868.1607472610-1682001233.1605902711

Buy Clean California Act. (2021). State of California. Retrieved from https://www.dgs.ca.gov/PD/Resources/Page-Content/Procurement-Division-Resources-List-Folder/Buy-Clean-California-Act

Green Stimulus: Support the economy, boost local jobs and cut carbon with upfront carbon caps on infrastructure projects. (2020). Mantle Developments. Retrieved from https://mantledev.com/insights/embodied-carbon/green-stimulus/

Canadian businesses and jobs at risk due to COVID-19. (2021). Canadian Federation of Independant Business. Retrieved from https://www.cfib-fcei.ca/sites/default/files/2021-01/Businesses-and-jobs-at-risk-due-to-COVID19.pdf

Small Business Everyday. (March 9, 2021). Small Business Recovery Dashboard. Retrieved from https://www.smallbusinesseveryday.ca/dashboard/

Indie Impact Study Series. (2012). Civic Economics. Retrieved from http://www.civiceconomics.com/indie-impact.html

Patel, A. n.d. Buying Local: An Economic Impact Analysis of Portland, Maine. Bowdoin College. Retrieved from https://berks.psu.edu/sites/berks/files/campus/Patel.pdf

Key Small Business Statistics – November 2019. (2019). Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/061.nsf/eng/h_03114.html

Producer responsibility for Ontario’s waste diversion programs. (2019). Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks. Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/page/producer-responsibility-ontarios-waste-diversion-programs

A proposed integrated management approach to plastic products to prevent waste and pollution Discussion Paper. (2019). Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/eccc/documents/pdf/cepa/proposed-approach-plastic-management-eng.pdf

Sustainability Primer. (2015). Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-05/documents/sustainability_primer_v9.pdf

The Supplier Selection Process. (2009). Business Link UK. Retrieved from https://www.infoentrepreneurs.org/en/guides/supplier-selection-process/

Xerox Global Citizenship Report. (2007). Xerox Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.xerox.com/downloads/usa/en/x/Xerox_Global_Citizenship_Report_2007.pdf